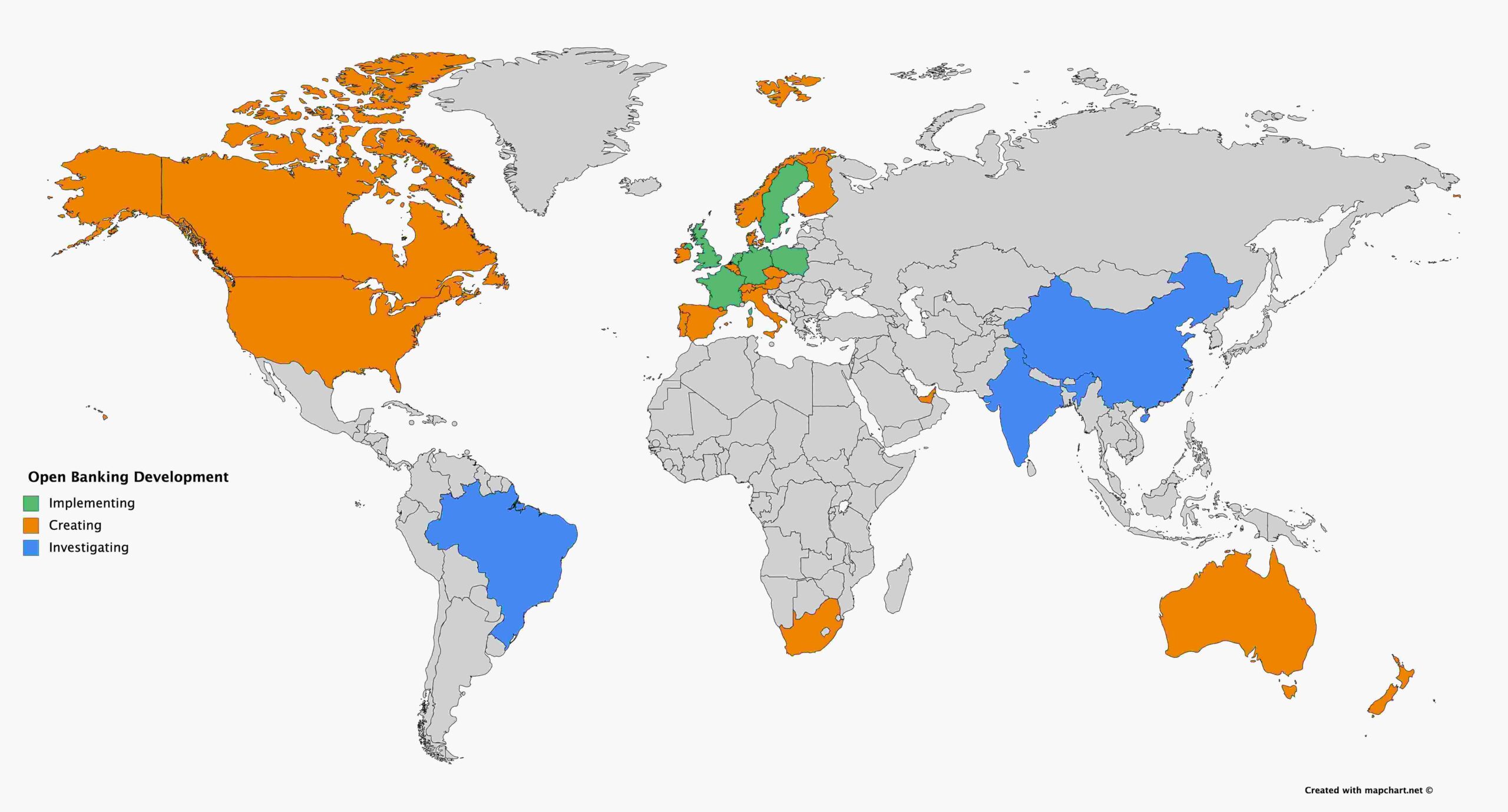

If you believe the press, 2019 is the year Open Banking will “revolutionize” the financial services industry and give us access to tools and technologies that’ll help us run our lives like never before. Whether you believe the hype or not, Open Banking is having a major impact on how banks and financial institutions do business. The financial services industry regulations driving it are serving as a catalyst to catapult banks into the API Economy with open APIs.

Historically, many financial institutions considered Web APIs in general as a threat to their operation. This was due to the need for open interfaces – which many banks did not support and viewed as a significant security risk – and security models that allow consumers to share information with other third parties outside the bank’s direct control. These threats are largely being dispelled by both the success of the API Economy in general, and the increasing willingness of financial services protagonists to deliver public APIs to meet their commercial goals. Even though we are still in the early days, this willingness only serves to extend what could be achieved through Open Banking.

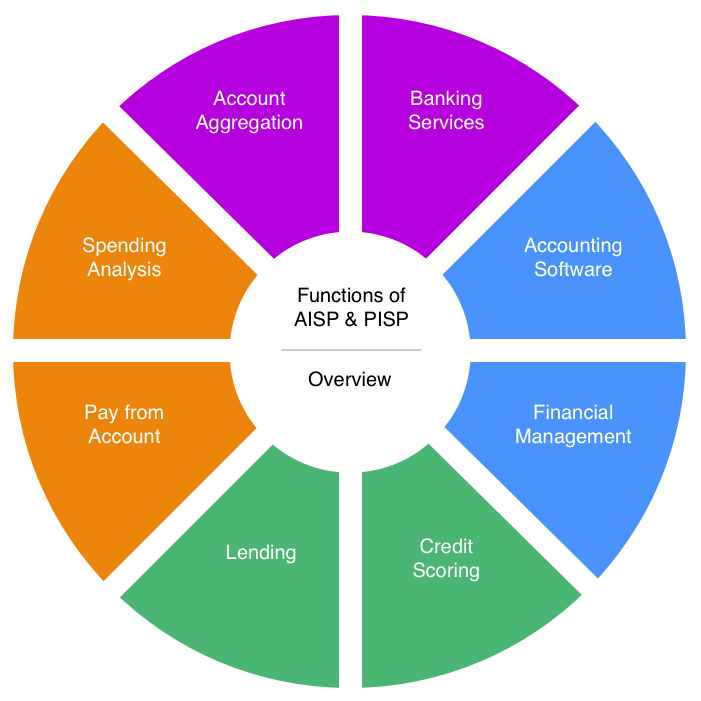

The idea of Open Banking has been around in various guises for a number of years and has been widely championed by the Open Bank Project and other first movers from the banking side like BBVA. It leverages the concept of banks being a banking services provider, with functions of the bank – opening and maintaining an account, making payments, and so on – being decomposed and consumable in a more fine-grained way. The “Open” in Open Banking tends to focus on these services being available via an open API.

There are many reasons why this is considered a great idea but first-and-foremost is that breaking down the functions of a bank into its component parts will help offer choice to the consumer. Obviously, an API doesn’t offer the consumer choice directly – they typically don’t build software – but it allows third parties their choice to act securely on their behalf. Consumers can therefore still hold an account with a bank, but consume a multitude of services from other organizations that their account-holding bank may not offer. Open Banking, therefore, becomes a means to drive a financial services ecosystem, with the choice of the consumer at the heart of what is offered.

This is where regulation comes into the picture. The market for third-party access to customer accounts exists already and customers can share their data through bilateral agreements or screen scraping internet banking (supported by organizations like Yodlee). However, coverage is piecemeal as it is based on both the appetite of banks to strike bilateral agreements and open suitable interfaces or the ease with which screen scraping can be implemented. Moreover, screen scraping is viewed by many in the industry as inherently insecure. This is due to the fact that a customer typically gives up both their internet banking credentials and access to all their data to the third party who performs the scraping. Given the differences in each internet banking implementation, it also falls short of providing banking customers with the same access across all their accounts, regardless of who they are held with.

Extending this choice is one of the main goals of the regulations that have been created to increase competition in financial services and is implicitly encouraging the development of Open Banking. Probably the most significant legislation is in Europe where Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2) has introduced new, third-party roles to financial services (more on these roles later). Coupled with PSD2 are the Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS) that define the requirements for how authentication of participants takes place. Essentially, these two pieces of legislation are helping shape Open Banking and form the major standards across Europe – UK Open Banking, the Berlin Group, and STET.

By proxy regulation is directly influencing the design of the Open Banking APIs. Whilst not an exact science, API design – with the two main influences of REST and what’s come before in financial services – follows familiar themes. We are therefore likely to find similar decisions being made by various groups in the construct of API endpoints, parameters, definitions and so on. Given that the standards initiatives are a reaction to the regulations put in place, a number of observable patterns have emerged within API design.

Design Patterns

Patterns in software design are a reusable solution that are intended as a means to deliver a solution that, given the right context, can be employed again and again. Patterns are nothing new – they were invented 40 years ago, and first applied to software in 1987. However, each evolution in a given industry or technology brings with it the opportunity to identify a suite of patterns that have the potential to be reused. This is certainly true of Open Banking.

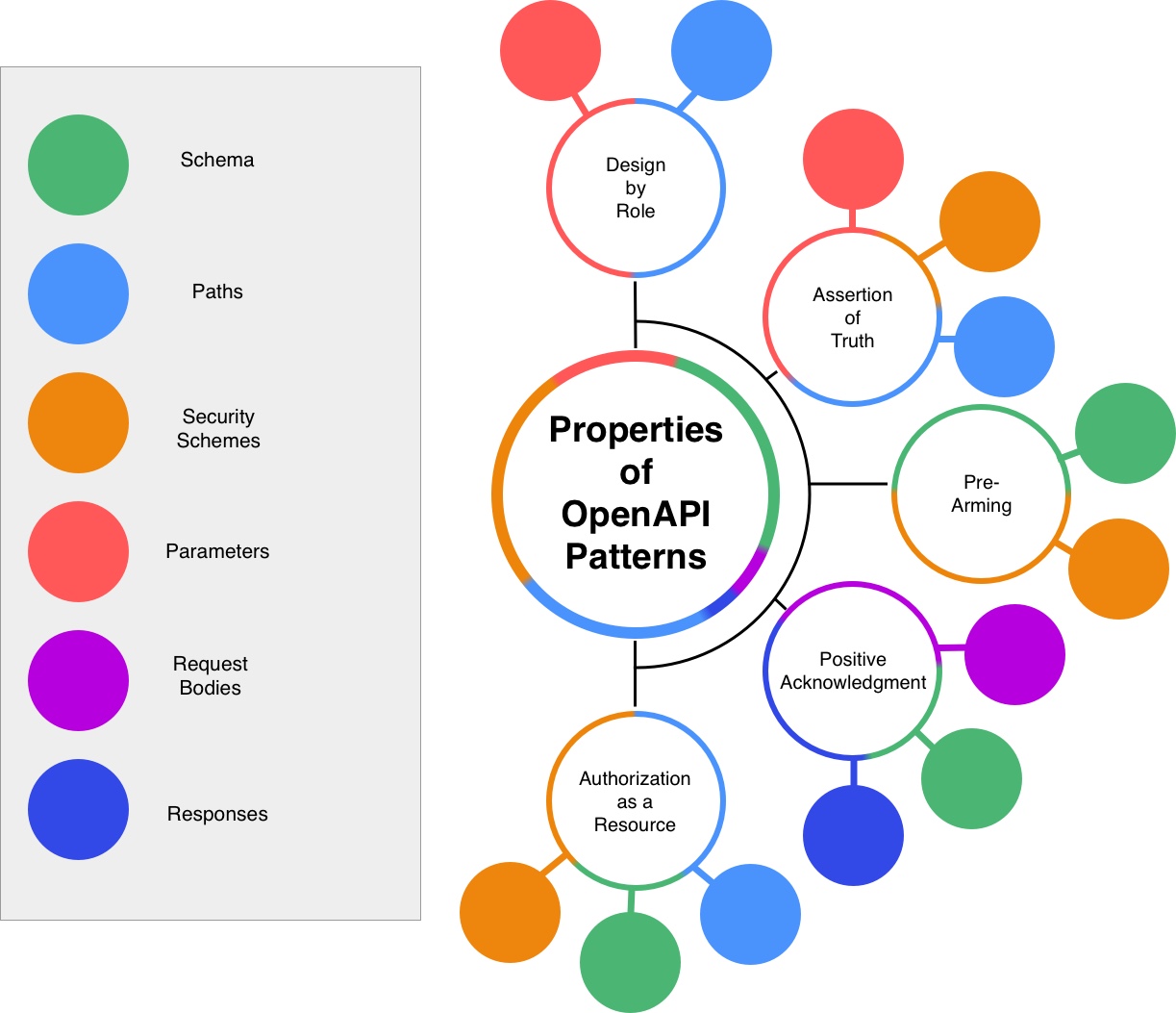

The European standards are currently the most mature and enumerate a number of design patterns. Whilst there are doubtless more patterns, the following are arguably the most prevalent:

- Design by Role

- Positive Acknowledgement

- Assertion of Truth

- Pre-Arming

- Authorization as a Resource

Each of these reflects either an aspect of the regulation or a common theme in financial services, which we’ll go into in more detail in the sections below.

Design by Role

We’ve already touched on the fact regulation is driving the Open Banking market forward and how new, third-party roles that are not the account holding organizations are being introduced. In the context of the European standards, PSD2 defines two roles – collectively referred to as Third Party Providers (TPPs) – that are intended to introduce competition and innovation to financial services, namely:

- Account Information Services Provider (AISP): TPPs that can, when authorized, access a customer’s bank account and use that information to provide services the customer wants.

- Payment Initiation Services Provider (PISP): Analogous to an AISP, but authorized to initiate a payment on the customer’s behalf.

Organizations can apply to become an AISP, PISP or both with the National Competent Authority (NCA) who are in charge of regulating financial services in each of the countries in the EU – for example, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the UK.

The need to regulate the activities of AISPs and PISPs according to the role they are authorized to perform has resulted in the Design by Role pattern. This pattern is based on the need – perceived or otherwise, and often formed through legal interpretation – for the standards to offer specific APIs or endpoints for specific roles, which has a demonstrable impact on the design.

The Berlin Group standard, for example, offers endpoints for both the type of payment instruction (termed “service”) – payments, bulk-payments or periodic-payments – and the type (termed “product”) – for example SEPA, ISO 20022 Payment Initiation, and so on. This is directly reflected in the construct of the API:

paths:

'/v1/{payment-service}/{payment-product}':

post:

summary: Payment initiation request

description: > This method is used to initiate a payment at the ASPSP.Whilst the request body for this operation is common to all services and products, this mechanism reflects the premise that the endpoints reflect what the PISP is allowed to “do” when calling the API. The approach almost smacks of SOA and SOAP, where payload and optionally URL reflected a given business operation rather than the creation or change in state of a resource.

The Design by Role is found in all the European standards. For example, in the STET standard there is a dedicated endpoint for payment requests tagged “PISP”:

/payment-requests:

post:

operationId: paymentRequestsPost

tags:

- PISP

summary: Payment request initiation (PISP)The UK Open Banking standard on the other hand provides endpoints dedicated to domestic payment, international payments, variations for scheduled payments, and file-based payments. The standard also “namespaces” the APIs to a specific role by enforcing a basePath in the API specification:

basePath: /open-banking/v3.1/pispThe UK standards also introduce specific OAuth scopes matching the roles - payments and accounts. This design approach separates a payment from the result – a recorded transaction – which is manifested as a transaction resource in the Account Information API and is only available to TPPs allowed to act as an AISP.

There are good reasons that the standards bodies took these regulation-driven design decisions. However, for the API designer, it becomes harder to create API specifications that are driven solely by REST. If you look at non-regulatory initiatives like the Open Bank Project you find attempts to pull resources together in a sensible manner (the Open Banking Project implements a transaction as a nested resource, which has other implications that we won’t go into here).

Designers need to keep in mind that payments systems are complex and retrofitting REST APIs is difficult – a pragmatic approach is essential. To that end, HATEOAS – whether full-blown adherence or a simple nod – can also help and designers should make use of it where possible. For example, the UK Open Banking standard implements JSON API so banks can extend the standard and provide links between – for example – a payment resource and the related transaction in the Account Information API. Extending and improving on this to include many different links, each to a relevant resource, greatly enhances the usability of the APIs on offer.

Positive Acknowledgement

Design by Role shows that the regulations and existing practices in financial services interfaces have a demonstrable effect on the design of endpoints. The same is true for the resources being defined. Fieldings original dissertation on REST typically promoted a “less is more” spirit and well-designed REST APIs tend to follow this, taking advantage of HTTP to communicate state between the client and the service. In particular, they tend to return “just enough” data to communicate state accurately to the client, with the view that for certain operations the client already “knows” about the state of a resource.

The go-to example of this is the design of responses to operations that implement the PUT and PATCH HTTP methods. When a designer implements these methods the server can safely assume the client needs only an acknowledgement that the operation has completed successfully. The client already has an accurate picture of the state of the resource by virtue of the fact they are updating all or some of a resource they know about. In such cases, the API designer can use a 204 – No Content – to indicate the operation was completed successfully, omitting a body from the response.

APIs in Open Banking – and financial services in general – tend to implement a different approach. Rather than making assumptions about the client’s knowledge of a given resource, the preference is to replay the updated resource to the client. This is the Positive Acknowledgement pattern. Whilst this is suboptimal in terms of bandwidth utilization, the idea is to ensure that the client is perfectly aware of the state of the resource, regardless of what they already know, so room for interpretation is minimized. The pattern is also critical to the Assertion of Truth pattern which we’ll go into next.

In terms of practical API design approaches, the Positive Acknowledgement pattern should manifest itself in a series of objects that can be reused in whole or in part, depending on whether PUT or PATCH is the prescribed method. The goals are threefold:

- Create an object where all properties are optional.

- For implementing PUT operations reuse the object and enforce mandatory properties as required.

- For PATCH reuse the object so a client can send only properties that are changing (in the style of and possibly implementing JSON Merge Patch).

In the context of the OpenAPI Specification, this approach often manifests itself in the use of the allOf keyword. The example JSON Schema object below is taken from the UK Open Banking Event Notification API standard, which uses the OBCallbackUrlData1 in a PUT operation to update a registered Callback URL. By applying this pattern we’d remove the required property from the object:

OBCallbackUrlData1:

type: object

properties:

Url:

description: >-

Callback URL for a TPP hosted service. Will be used by ASPSPs, in conjunction with the resource name, to

construct a URL to send event notifications to.

type: string

Version:

description: Version for the event notification.

type: string

minLength: 1

maxLength: 10

additionalProperties: falseFor a PATCH operation, the object can be reused as-is with the additionalProperties keyword preventing properties not defined in the specification from being created in the payload. For a PUT operation we’d combine this with mandatory constraints using the allOf keyword:

CallbackUrlPatch:

allOf:

- $ref: '#/definitions/OBCallbackUrlData1

- required:

- Url

- VersionBy taking this approach, API designers can make good use of the reuse opportunities that the OpenAPI Specification offers, avoiding bloat in their specifications and ensuring they their documents remain as concise as possible.

Assertion of Truth

Assertion of Truth – generally known as the somewhat impenetrable term non-repudiation – is the idea that an API consumer or provider can provide evidence that the request for, or response to an API call cannot be disputed. In the world of financial services and regulation-driven development, this is an important feature of how liability is apportioned to the participants in a financial system. If an assertion of truth is made that cannot be disputed, it is straightforward to assign fault or understand who owes what for a given payment or payments.

In a practical sense, Assertion of Truth in API design terms is offering cryptographic proofs through message signing, plain and simple. Messaging signing is a design approach found in most financial and payment systems around the world. In the context of Open Banking standards, API request and responses are signed for activities like payment initiation or application errors that may result in financial cost for API consumers. Message signing in the context of the European standards follows two main approaches:

- The JSON Object Signing and Encryption (JOSE) framework, in particular the use of JSON Web Signatures – normally referred to by their root object, JSON Web Tokens (JWT) – has been adopted by UK Open Banking. Without going into too much detail, JSON Web Signatures (JWS) are like XML Signatures in that they wrap the data within a signing structure that delivers a self-describing assertion of truth and validity.

- HTTP Signatures are used by both Berlin Group and STET. HTTP Signatures provide the same assertion of truth, but by providing the signature as a HTTP header rather than as an encapsulation of the data.

For the API designer, both approaches have implications:

- JWS are inherently hard to represent in OpenAPI description documents, which is due to the fact that it is difficult to represent three BASE64 encoded strings separated by periods in the underlying JSON schema.

- In contrast, HTTP Signatures are easy to represent in an OpenAPI description document – they are simply a HTTP Header – and designers can represent their payloads as native JSON Schema. However, at an implementation level, they lack the encapsulation benefit that JSON Web Signatures provide.

There is therefore little to say on HTTP Signatures. For JWS, the UK Open Banking standards show a number of ways to express them in an OpenAPI description document. Admittedly, these might be viewed as workarounds for the lack of formal JOSE support in OpenAPI, but they do provide useful examples of the approach.

Detached Signatures

Detached signatures are a means for providing a JSON Web Signature whilst still being able to express the request or response payload as a Schema object. The steps for the developer are threefold:

- Construct the JWS.

- Remove the payload and send as a HTTP Header called

x-jws-signature. - Send the payload as a regular JSON object.

To follow this method, the API designer needs only to define the x-jws-signature header in their API specification, whilst API consumers must follow an implementation guide to understand exactly how the approach should be implemented.

Implied Signatures

In this approach, the schema only implies that request or response is a JSON Web Signature by defining the payload as a regular JSON definition and then using an appropriate content type to describe it. In an OpenAPI description document, this is accomplished by using the content keyword:

200:

description: OK

content:

application/jws:

schema:

type: stringThis approach – coupled with appropriate documentation for the API consumer – allows the designer to indicate their intent whilst still delivering an informative API specification.

Pre-Arming

Open Banking is introducing some interesting challenges to financial services and none more so than the ability for third parties to make requests for data and services that were formally always between the bank and it’s customer. This has a number of implications, one of which is the need to capture information about what a consumer wants to do with their account before the bank actually knows who they are. This is where the Pre-Arming pattern materializes.

The Pre-Arming pattern manifests itself as the means for a TPP to send a complex set of information to an API-providing bank prior to a real person identifying themselves with the bank and delegating authority to access the account to the TPP. That real person – the customer of both the TPP and the bank – is engaging with the TPP for a service, such as initiating a payment, and they need to authenticate with the bank to give access to their account. There’s some significant advantages to this approach:

- A rich data set can be captured without shoehorning it into existing protocols.

- Additional layers of security can be added to help minimize the ability of unsolicited requests to be made.

- Data can be sent outside the consumer authorization flow (something we’ll touch on below) which means the authorization can happen in a graceful manner.

When Open Banking standards started to coalesce, the API designers took these needs into account and added methods into their flow. For example, all the major European standards include the means to transmit consumer authorization – or Consent – to the bank. These mechanisms are increasingly being coupled with protocols that help bind the request with the security requirement, such as the Financial API standards.

In view of this pattern the API designer has to be cognizant of two factors:

- The need to provide API endpoints that allow such requests to be made.

- The ability to allow these requests to be made without delegated authority from the consumer, with TPP’s application having sufficient rights to do so.

The UK Open Banking standard exemplifies this through their Consent endpoints. For example, the Account Access Consent endpoint is a POST that contains a record of what access a consumer provided to a third party (note this is shown without the JSON API wrapper):

OBReadData1:

type: object

properties:

Permissions:

items:

$ref: '#/definitions/OBExternalPermissions1Code'

type: array

description: >-

Specifies the Open Banking account access data types. This is a list of the data clusters being consented by the

PSU, and requested for authorisation with the ASPSP.

minItems: 1

ExpirationDateTime:

description: >-

Specified date and time the permissions will expire.

If this is not populated, the permissions will be open ended.

All dates in the JSON payloads are represented in ISO 8601 date-time format.

All date-time fields in responses must include the timezone. An example is below:

2017-04-05T10:43:07+00:00

type: string

format: date-time

TransactionFromDateTime:

description: >-

Specified start date and time for the transaction query period.

If this is not populated, the start date will be open ended, and data will be returned from the earliest

available transaction.

All dates in the JSON payloads are represented in ISO 8601 date-time format.

All date-time fields in responses must include the timezone. An example is below:

2017-04-05T10:43:07+00:00

type: string

format: date-time

TransactionToDateTime:

description: >-

Specified end date and time for the transaction query period.

If this is not populated, the end date will be open ended, and data will be returned to the latest available

transaction.

All dates in the JSON payloads are represented in ISO 8601 date-time format.

All date-time fields in responses must include the timezone. An example is below: 2017-04-05T10:43:07+00:00

type: string

format: date-time

required:

- Permissions

additionalProperties: falseThis is transmitted to the bank without consumer authorization so an appropriately secure means to deliver it must be provided. This is accomplished using a mutually authenticated TLS connection and an OAuth 2.0 Client Credentials grant, which is defined in the specification:

TPPOAuth2Security:

type: oauth2

flow: application

tokenUrl: 'https://authserver.example/token'

scopes:

accounts: Ability to read Accounts information

description: TPP client credential authorization flow with the ASPSPThe third party will therefore obtain an access token using the Client Credentials grant from the bank’s Token endpoint, granted an appropriate scope to perform this operation.

The Pre-Arming pattern, therefore, helps with the delivery of information about a consumer to bank. It is of particular importance as it dovetails with the Authorization as a Resource pattern that is used to convey what a customer actually wants to do.

Authorization as a Resource

Authorization is possibly the most important and contentious topic in the development of Open Banking in Europe. The impact of the regulations on the incumbent banks and how they hold, store, and manage their customers data – and who else is authorized to access it – has resulted in significant changes for banks in how they share their customers data. They are charged by the regulations – in this case, also influenced by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – with providing data or initiating payments from accounts based on clear and explicit instruction communicated by the customer to the TPP.The idea of capturing what a customer has authorized a TPP to access from their account is normally wrapped up in the idea of Consent, and this has lead to the development of the Authorization as a Resource pattern. In essence, Authorization as a Resource encapsulates the access a customer has granted a TPP in explicit terms. The is due to the general perception – in the security-focused part of the Open Banking community at least – that constructs like OAuth scopes are not suitable for this purpose, for a number of reasons:

- They are not verbose enough to describe what a customer of a bank is actually consenting to, being largely coarse grained.

- They are transient in nature with limited means of establishing an audit trail.

- In most security products they are not divorced from the actual data they permit access to.

- There is limited means to implement an Assertion of Truth pattern, which is important for stating indefatigably what the customer of the third party and the bank have consented to.

The APIs therefore provide the means to describe these properties and this is how the Authorization as a Resource pattern manifests itself.

We’ve already touched on the Account Access Consent example from the UK Open Banking. The Pre-Arming pattern allows the consent data to be sent to the bank to authorize access to the account using appropriate means such as their internet banking credentials. Authorization as a Resource allows the consent they’ve given to the third party to be played back in a verbose, easily understandable manner.

Of particular relevance in the Schema Object shown is the definition of OBExternalPermissions1Code. This details the permissions that the customer is giving to the third party when accessing their data. In the UK example, this is an array based on an enumeration of permission codes:

OBExternalPermissions1Code:

description: >-

Specifies the Open Banking account access data types. This is a list of the data clusters being consented by the

PSU, and requested for authorisation with the ASPSP.

type: string

enum:

- ReadAccountsBasic

- ReadAccountsDetail

- ReadBalances

- ReadBeneficiariesBasic

- ReadBeneficiariesDetail

- ReadDirectDebits

- ReadOffers

- ReadPAN

- ReadParty

- ReadPartyPSU

- ReadProducts

- ReadScheduledPaymentsBasic

- ReadScheduledPaymentsDetail

- ReadStandingOrdersBasic

- ReadStandingOrdersDetail

- ReadStatementsBasic

- ReadStatementsDetail

- ReadTransactionsBasic

- ReadTransactionsCredits

- ReadTransactionsDebits

- ReadTransactionsDetailHowever, not all the European standards follow this means of delivering the Authorization as a Resource pattern. For example, the Berlin Group standard explicitly defines what accounts are available, with more-coarse grained permissions for each data cluster. The consent request, therefore, is a simple list of data clusters and accounts, as shown in the example in the Berlin Group specification:

consentsExample_DedicatedAccounts:

description: Consent request on dedicated accounts

value:

access:

balances:

- iban: DE40100100103307118608

- iban: DE02100100109307118603

currency: USD

- iban: DE67100100101306118605

transactions:

- iban: DE40100100103307118608

- maskedPan: 123456xxxxxx1234

recurringIndicator: 'true'

validUntil: '2017-11-01'

frequencyPerDay: '4'The examples show that there are multiple ways of fulfilling the Authorization as a Resource pattern and API designers are going to need to understand both the regulatory context and the needs of the community in implementing the most appropriate model.

However, API designers should also consider what can be achieved using security protocols rather than dedicated endpoints in the API. In essence, there is nothing to say that the designers of the API were right in shunning the idea of using OAuth scopes to drive permissions and there is an opportunity to revisit this. A well-designed set of scopes, coupled with enhanced capabilities available in OpenID Connect and some appropriately detailed API documentation might work just as well. As the market evolves there is an opportunity for designers to look at this option rather than simply replaying the pattern from the existing standards.

Final Thoughts

We’ve focused largely on Europe in this piece but other markets – notably Australia – are hard at work and the genie is definitely out of the bottle as they start out on their Open Banking journey. In the short term, the core patterns we’ve talked about here are likely to evolve. As the standards change and are incorporated into more commercially focused APIs, a number of themes will emerge:

- API and security standards will start to merge with API specifications being able to more effectively represent and express the JOSE suite, HTTP signatures, and so on. As this evolves, API designers will be able to effectively communicate their design decisions in a single document.

- As financial services becomes more comfortable with its place within the API Economy, the Positive Acknowledgement and Assertion of Truth patterns will becomes less prevalent and will morph into something that does not involve transmitting the entirety of a resource over the wire.

- Authorization as a Resource will becomes more sophisticated and expressive as the needs of consumers are piqued by the increasing number of third-party services the Open Banking ecosystem offers them. The ability to express a range of services and the parameters within which they operate will become apparent. Indeed, API designers may exploit technologies more suited to fine-grained consent management to express the interface to their services. A good example is taking advantage of the Request parameter available in OpenID Connect Hybrid Flow, which could remove the need for the Authorization as a Resource pattern altogether.

However, as the market grows, the influence of regulation on API design will also start to decrease. The financial services industry will reach a point where every participant has APIs. The hard yards of creating the banking API platforms will be complete and the product teams at banks and financial institutions will realize the potential of what they now have. Regulation is serving to level the playing field, firmly entrenching banking as a sector of the API Economy and making ground in place of commercial pressure. Once regulatory commitments have been met, the protagonists will seek to take advantage of their API-enabled platforms to differentiate their products, offering APIs created to meet market demand.

New patterns will therefore emerge that are a reflection of commercial decisions rather than legislative mandate. We’ll see banks taking on the role of banking service providers, delivering APIs to the ecosystem that are a reflection of what API consumers really want. With that will come API designs that are unique and tailored to their product offerings, coupled with API styles – GraphQL, gRPC, or the next big thing – that are the best fit for delivering on the promise of Open Banking.